Freeway Free on the Snake River: Locked In, Locked Out

Our boat goes through our first lock – 80 feet or more down from one level of the Snake to the next. We move into the lock; a bridge is before us, an open space behind. Then a wall seems to rise from beneath the river behind us as the water level in the lock is let out and we begin to descend. The walls rise, only two feet from the boat on either side. The bridge before us is now far above, with a large and getting ever higher curving wall ahead. We descend and descend. The black wall behind us is holding back the river, though it appears there are leaks. The black wall ahead is now 80 feet high. On the side are dripping black concrete blocks a yard high piled up and up. Finally we stop descending. We wait. There is a loud shudder, and a crack appears in the wall ahead. Sunlight, and color, a view of hills and sparkling water. The crack opens wider – the feeling is like the scene in “The Wizard of Oz” where Dorothy steps out of the sepia-toned world of Kansas into a technicolor Oz. The engines throb and we move forward into the light and space.

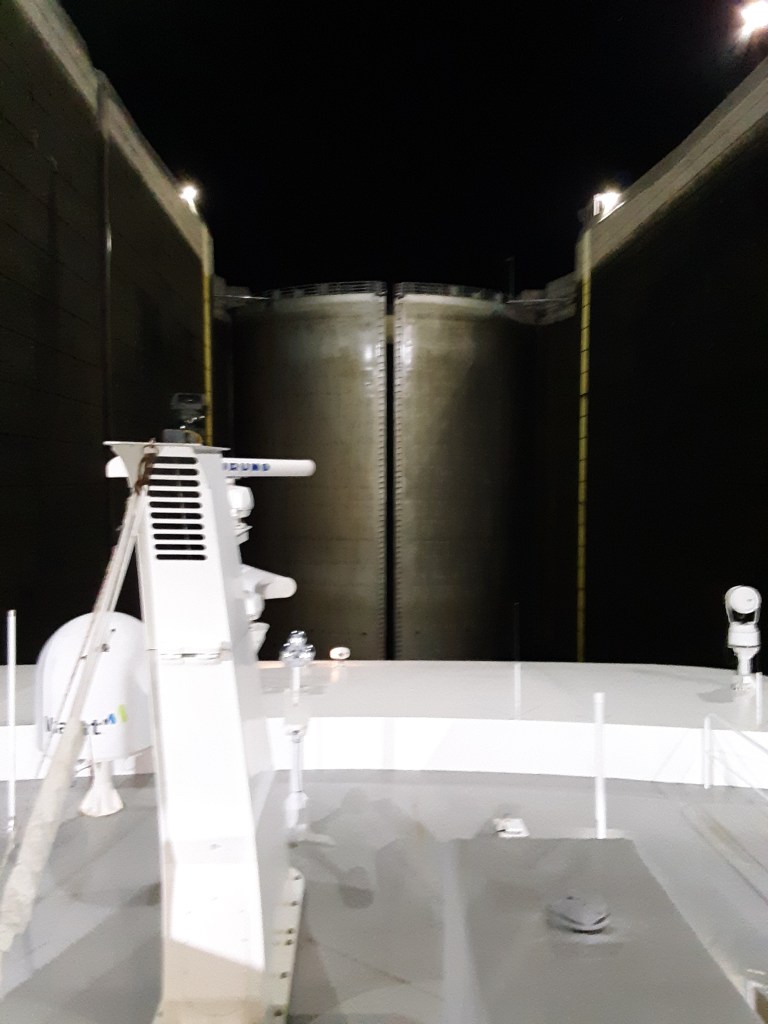

We go through a second lock at night – it is still magical. There is only black and white, the white boat, the black night, the gleaming gate, the sparkling water.

Later we explored off the boat at the Bonneville Dam, whose Visitor Center is a self-congratulatory celebration of the transformation of the wild rolling Columbia river into “a damn fine machine” for generating hydropower, in the words of an industry lobbyist.*

We saw another aspect of the locks and dams at the fish hatchery, where tiny salmon fry are nurtured until they are large enough to release downstream from the dams and make their way to the sea, and at the fish ladder, where returning salmon are given a chance to circumvent the dam in a series of cascades. These makeshift replacements of natural features are an attempt to appease the fishermen and native peoples whose lives depend on the salmon run. In another section of the hatchery, a bit off the self-guided tour, the sight of frustrated salmon leaping in vain against a current backed by a three-foot fence made me sad. In the hatchery these fish are artificially milked for their semen or eggs before dying, so the salmon fry can be created. The salmon would die anyway after spawning, but as they frantically jumped over and over against the impassable barrier, theyseemed to know they are supposed to get further to their spawning grounds than a hatchery.

===

*Quoted from Blaine Harden’s A River Lost; the Life and Death of the Columbia